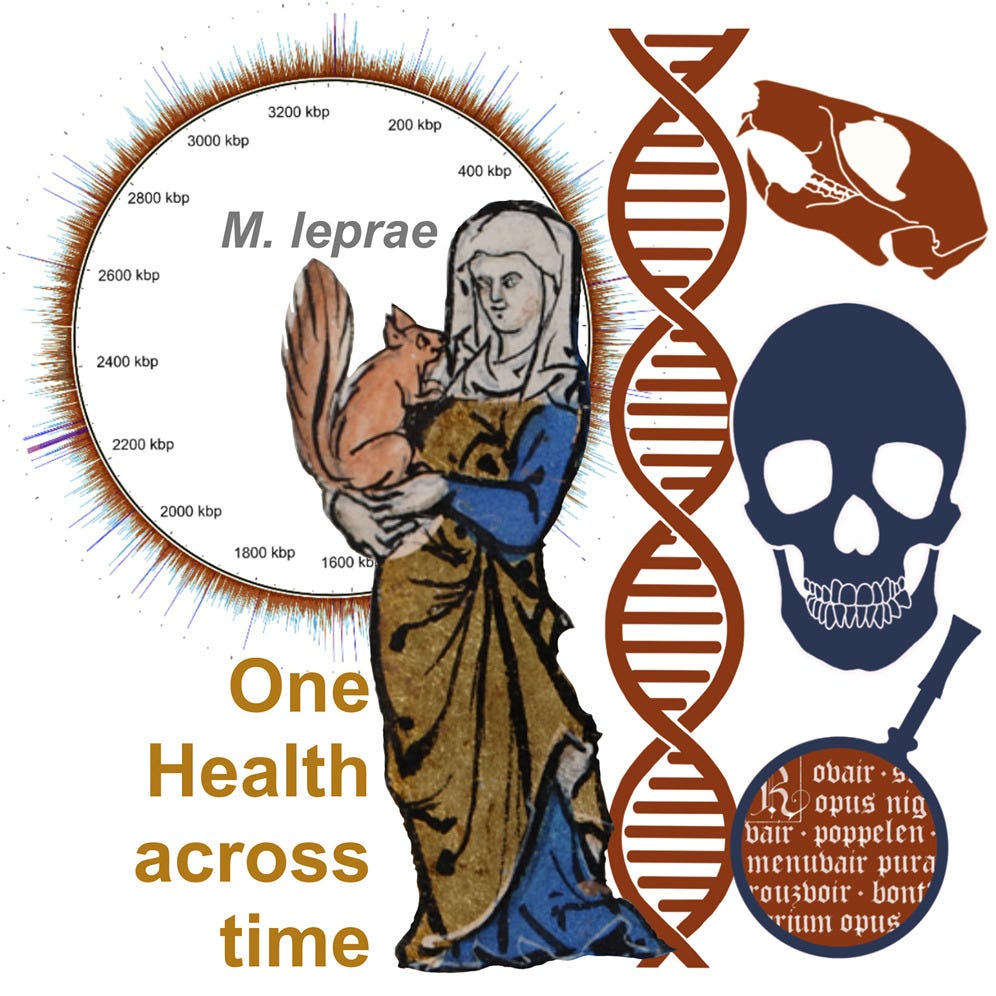

Leprosy, an ancient scourge, has haunted humanity for millennia. With roots tracing back to ancient India and China, this disease continues to persist in various parts of the world. While modern medicine has made strides in understanding and treating leprosy, the role of animal hosts in its transmission remains an area of ongoing investigation. The recent COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of zoonotic diseases, those capable of spreading from animals to humans. A groundbreaking study by Urban and colleagues is now shedding light on the historic role of animals in leprosy transmission, using a One Health approach that integrates archaeology, history, and biology.

This article delves into the fascinating discovery of medieval squirrels as potential carriers of leprosy, exploring the implications of interspecies transmission and the insights gained from ancient DNA analysis. We’ll examine how the study, published in Current Biology, uncovers the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health, offering valuable lessons for managing and potentially eradicating leprosy today. Through a blend of historical context and scientific findings, we’ll unravel the intriguing story of squirrels, leprosy, and the medieval world.

Zoonotic Diseases and Leprosy

Zoonotic diseases, those transmitted between animals and humans, have gained increased attention in recent years. Leprosy, primarily caused by the bacteria Mycobacterium leprae (M. leprae), is known to have animal hosts, including armadillos, chimpanzees, and red squirrels. The disease can cause nerve damage, skin lesions, and other debilitating symptoms. Despite being rare in many parts of the world, leprosy persists in regions of Asia, Africa, and South America, with over 200,000 new cases reported annually.

The origins of leprosy are debated, with evidence pointing to either Eastern Africa or India. From these regions, the disease spread through trade and military campaigns to the Middle East, Europe, and beyond. By the Middle Ages, leprosy had become widespread throughout Europe, prompting the establishment of leprosariums to isolate those afflicted. The recent study highlights the importance of understanding historic zoonotic transmission to better address the disease’s current prevalence.

The Medieval Era and the Squirrel

During the medieval period, squirrels were commonly kept as pets and utilized in the fur trade. Squirrel fur, often imported from Scandinavia, Eastern Europe, and Russia, was highly valued for lining and trimming garments. Depictions of people adorned in squirrel fur are prevalent in medieval art and literature. The sheer volume of squirrel skins imported during this era underscores the significant role these animals played in the medieval economy and daily life. Beyond their use for fur, squirrels were also cherished as pets, particularly by nuns and other religious figures.

The close proximity between humans and squirrels during the Middle Ages created ample opportunities for disease transmission. The city of Winchester, a major trading hub with a known furrier industry and a leprosarium, provides a compelling case study for exploring the potential link between squirrels and leprosy. Archaeological excavations in Winchester have revealed the presence of squirrel bones in furriers’ workshops and leprosy-associated lesions in individuals buried at the leprosarium.

The Study Outcomes

Urban and colleagues conducted a comprehensive analysis of archaeological remains from Winchester, employing ancient DNA (aDNA) sequencing to detect M. leprae in both human and squirrel samples. Their findings revealed the presence of leprosy bacteria in both populations, with the strains belonging to the same genotype. This groundbreaking discovery provides direct evidence of interspecies leprosy transmission between medieval humans and squirrels.

The researchers successfully reconstructed several new M. leprae genomes, including one from a Eurasian red squirrel. While it remains unclear whether squirrels initially transmitted leprosy to humans or vice versa, the study’s results highlight the potential for animal hosts to play a significant role in the spread and persistence of the disease. These findings have important implications for understanding the diversity of leprosy strains and the dynamics of transmission between animals, humans, and the environment.

Implications for Modern Medicine

The study conducted by Urban and colleagues underscores the value of interdisciplinary approaches to understanding complex medical issues. By integrating archaeological, historical, and biological perspectives, the researchers were able to definitively demonstrate leprosy transmission between medieval humans and squirrels. This One Health approach has the potential to inform future medical debates and shed light on the role of animal hosts in the continued persistence of leprosy in the modern day.

As a zooarchaeologist, the implications of this study are particularly intriguing. The ability to identify markers of disease in animal bones and apply this information to biomedical research opens up new avenues for investigating the interplay between humans, animals, and disease. The One Health method holds immense promise for future medical studies, offering a holistic perspective on the interconnectedness of health across species and environments.

Conclusion

The discovery of medieval squirrels as potential carriers of leprosy offers a fascinating glimpse into the complex history of zoonotic diseases. The study by Urban and colleagues provides compelling evidence of interspecies transmission, highlighting the importance of considering animal hosts in the spread and persistence of leprosy. By employing a One Health approach, the researchers have demonstrated the value of integrating diverse disciplines to gain a deeper understanding of medical challenges.

The findings from this study have significant implications for modern medicine, informing future research on leprosy transmission and the role of animal reservoirs. As we continue to grapple with emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases, the lessons learned from this historical investigation can guide our efforts to protect human and animal health. The interconnectedness of humans, animals, and the environment underscores the need for collaborative, interdisciplinary approaches to address the complex challenges of disease prevention and control. Understanding our past is crucial to safeguarding our future.