When we think about cancer, our minds often jump to genetics, lifestyle choices, or environmental factors. We put on sunblock when we go out in the sun, avoid smoking, and install radon detectors in our homes. If we have a family history of cancer, we tend to worry about an ache or pain (or mass) we detect in an unusual part of our body.

Don’t get me wrong. That’s all fine and good. But did you know that certain viruses can cause cancer? While not every infection leads to a malignancy, a handful of viruses have been scientifically linked to specific cancers. These viruses, known as “oncoviruses,” have sparked interest because of their unique mechanisms and potential for prevention through vaccines and other strategies.

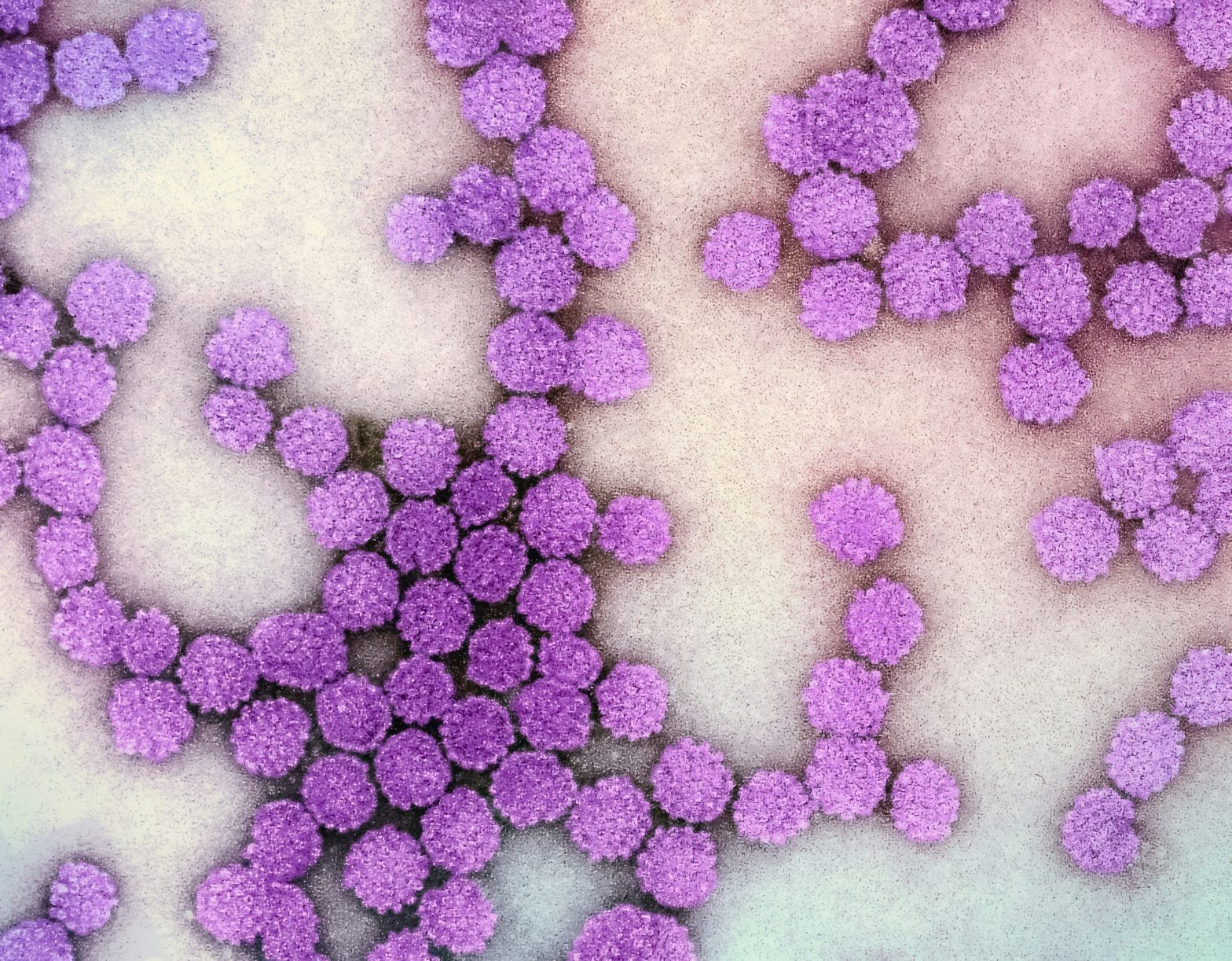

As with any other virus, prevention is key. But let’s also talk about what you can do if you are exposed and infected. So let’s go one by one, and talk about these nasty little pieces of enveloped (or not) genetic material that hijack your cells and cause disease.

How Viruses Trigger Cancer: The Mechanisms at Play

First, let’s talk about how these oncoviruses actually cause cancer. It doesn’t happen overnight. Instead, they use a combination of mechanisms, leading to genetic mutations and chronic inflammation that disrupt normal cell function, including a cell’s ability to self-destroy when it needs to.

Some viruses, like human papillomavirus (HPV) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), produce viral proteins called oncoproteins. These proteins interfere with key cellular processes, such as cell cycle regulation and apoptosis (programmed cell death). For instance, HPV’s E6 and E7 proteins disable tumor suppressor genes like p53 and Rb, paving the way for uncontrolled cell growth. Similarly, EBV produces proteins like LMP1, which promotes cell survival and proliferation.

Chronic infection is another critical factor. The chronic inflammation caused by chronic infection leads to repeated cycles of cell injury and repair, increasing the likelihood of DNA mutations over time. Chronic inflammation also creates an environment rich in reactive oxygen molecules, which can directly damage DNA. (This is also known as oxidative stress.)

Other viruses hijack the host’s immune system. They evade immune detection and alter cytokine signaling, creating a microenvironment that supports cancerous growth. (Cytokines are chemicals used by cells to communicate, or to destroy foreign cells and microbes.)

Some oncoviruses incorporate their genetic material into the host genome. This integration can disrupt normal cellular functions and trigger mutations that lead to malignancy.

Finally, retroviruses can activate oncogenes through insertional mutagenesis. That’s a fancy way to say that by integrating their genome near a host oncogene, these viruses push the host cell into overdrive. That leads to the unregulated multiplication of those cells.

Let’s look at these viruses in more detail.

Human Papillomavirus (HPV) — A Preventable Threat

Human papillomavirus, or HPV, is perhaps the most well-known cancer-causing virus. Linked to cervical, anal, and oropharyngeal cancers, HPV spreads through sexual contact. The United States sees around 14 million new infections each year, with persistent “high-risk” strains like HPV-16 and HPV-18 being the culprits behind most HPV-related cancers. These strains have a notorious role in nearly all cases of cervical cancer, a substantial portion of anal cancers, and an increasing number of oropharyngeal cancers, particularly in men.

Symptoms can range from genital warts to precancerous lesions, but often, infections are without symptoms (asymptomatic), silently persisting until complications show up. The good news? Vaccines like Gardasil effectively prevent infections from the most dangerous HPV strains. Vaccination campaigns have made strides in reducing cervical cancer incidence worldwide, as seen in Australia, which is on track to eliminate cervical cancer. However, the situation in the United States reveals persistent disparities that highlight the urgent need for equitable vaccination efforts.

Disparities in HPV Vaccination in the U.S.

Despite the availability of vaccines, vaccination rates are uneven across ethnic and socioeconomic groups in the United States. Studies reveal that Hispanic and Black populations, who face disproportionately higher rates of HPV-associated cervical cancer, are less likely to receive the HPV vaccine due to barriers such as limited healthcare access, cost, and cultural stigmas surrounding discussions of sexual health. These disparities are further exacerbated in rural areas, where access to preventive healthcare, including vaccines, is limited.

Notably, vaccination rates also vary by gender. Although HPV vaccines have been recommended for both boys and girls since 2011, girls continue to be vaccinated at higher rates than boys. This discrepancy may stem from the misconception that HPV-related cancers primarily affect women. However, HPV-related oropharyngeal cancers increasingly affect men, which now surpass cervical cancer in incidence in the U.S. Vaccinating boys is essential not only to protect them, but also to reduce transmission, achieving herd immunity.

Closing the Gap

To address these disparities, public health initiatives must prioritize equal access to HPV vaccination for all ethnic and socioeconomic groups. Strategies include offering the vaccine free of charge through federal and state programs, integrating vaccination education into school curricula, and tailoring outreach efforts to address cultural concerns and misconceptions. Targeted efforts in underserved communities, such as mobile vaccination clinics and multilingual health education campaigns, can help overcome barriers to access.

Equally important is the normalization of vaccination for boys. Public health campaigns must emphasize that HPV vaccination protects against many cancers, including those that disproportionately affect men. By reframing the conversation to include all genders, we can challenge stigmas and ensure that boys and girls alike are vaccinated at equitable rates.

The push for universal HPV vaccination is not just about reducing individual cancer risks; it’s about achieving health equity and protecting future generations. By addressing these disparities and fostering equal access, the U.S. has the opportunity to replicate Australia’s success in drastically reducing HPV-related cancers and ultimately eliminating cervical cancer. Let’s hope we get there one day, along with the rest of the world.

Hepatitis B and C — Silent Causes of Liver Cancer

Both hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) are major contributors to liver cancer. These viruses cause chronic infections that can lead to cirrhosis and eventually hepatocellular carcinoma (cancer of the liver cells). HBV spreads through bodily fluids, while HCV is primarily bloodborne, both often linked to needle sharing or unsafe medical or sex practices.

Symptoms of liver damage might not appear until the disease is advanced, emphasizing the need for regular screenings. Vaccines are available for HBV, offering robust protection, but no such option exists for HCV yet. For those already infected, antiviral therapies can suppress the virus and reduce the risk of cancer development.

Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) — The Versatile Oncovirus

Best known as the cause of mononucleosis, the Epstein-Barr virus is implicated in various cancers, including Burkitt’s lymphoma and nasopharyngeal carcinoma. It spreads through saliva, earning it the nickname “the kissing disease.”

Genetic susceptibility is one critical factor in EBV-related cancers. Environmental factors play an equally significant role. Immunosuppression is another crucial factor.

The Burden of EBV in Developing Nations

While EBV infections are ubiquitous, their consequences disproportionately affect developing nations, where environmental and healthcare challenges exacerbate the risk of EBV-related diseases. The lack of an EBV vaccine further compounds the burden in these regions.

Other Notable Oncoviruses

Human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8), also known as Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV), in contrast, has a more widespread but lower prevalence globally. Human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1), associated with adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL), is most common in specific endemic regions.

Prevention and Public Health Impact

While infection with an oncovirus significantly increases cancer risk, it’s important to note that cancer is a rare outcome. Prevention is the cornerstone of reducing virus-related cancers. In the U.S., virus-associated cancers account for about 10% of all cancer cases. Globally, these viruses underscore the diverse pathways through which infections contribute to cancer, and highlight global health inequities.

Additional Reading

- American Cancer Society. “Viruses That Can Lead to Cancer.”

- MD Anderson Cancer Center. “7 Viruses That Cause Cancer.”

- Australian Department of Health. “National Strategy for the Elimination of Cervical Cancer in Australia.”

- Clinical Microbiology Reviews. “Viruses and Human Cancers: A Long Road of Discovery.”

- Yale School of Medicine. “The Virus Behind the Cancer.”

While infection with an oncovirus significantly increases cancer risk, it’s important to note that cancer is a rare outcome. Factors such as genetic predisposition, immune status, and coexisting environmental exposures also play crucial roles in determining the progression from infection to malignancy.

Prevention is the cornerstone of reducing virus-related cancers. Vaccination, safe sex practices, clean needle use, and early screenings are all critical strategies. Public health campaigns, like those targeting HPV and hepatitis B, have made significant strides in lowering cancer incidences globally.

In the U.S., virus-associated cancers account for about 10% of all cancer cases. While this is lower than the global average, it underscores the importance of continuing research, improving vaccine access, and raising awareness. Globally, these viruses underscore the diverse pathways through which infections contribute to cancer, and highlight global health inequities.

Regions with high prevalence often coincide with areas of limited healthcare infrastructure, compounding the burden of these cancers. Addressing these challenges requires targeted public health interventions, improved diagnostic capabilities, and accessible treatments to mitigate the impact of these virally induced malignancies.