As a kid, I had a friend. One day, she smiled, and I noticed a horizontal line on her tooth. When I asked her about it, all she said was she had always had it but did not know why.

Many years later, I was studying how various diseases and stressors can be identified in bones. One of these stressors left lines on one’s teeth. These are called Linear Enamel Hypoplasia (LEH) and are caused when your tooth stops growing in periods of intense stress or trauma (i.e., starvation). When the tooth resumes growth, a line is left behind.

I do not think my friend was starved as a child, but she may have had some other intensely traumatic event occur that caused her tooth to show LEH.

While my friend likely was not starved, this is not necessarily the case for all children throughout history. We have a tendency to look into the distant past with rose-colored glasses. We imagine simpler times devoid of worries about paying rent, repaying student loans, and 5 o’clock traffic.

But history is messy, and children often had it the hardest.

A recent study by Dr. Luiz Pezo-Lanfranco and his colleagues examined the skeletal remains of 67 individuals from the Quebrada Chupacigarro Cemetery (QCC) in North-Central Peru. They found a high prevalence of health-disease processes during the transition between the Middle and Late Formative Periods (500–400 BC). Additionally, their study revealed a tragically high mortality rate, especially in < 3,5 year-olds.

But what exactly were these health-disease stressors they identified, and what could have caused them?

The Formative Period and QCC Cemetery

In the Central Andes of South America, the formative period (3000–1 BC) is characterized by a transition from a loosely stratified society to a more complex, hierarchical one. During the Initial Formative (3000–1800 BC) until the Middle Formative (1200–400 BC), powerful belief systems were linked by ceremonial centers across the Central Andes.

These theocratic governments were controlled by sovereigns of religious institutions that oversaw surplus, labor, and trade networks. Their power was legitimized and renewed via lavish feasts, awe-inspiring architecture, and dissuasive discourses.

During the last phase of the Middle Formative, these ceremonial centers could be identified by their shared Cupisnique/Chavín iconography and U-shaped architecture.

Cupisnique/Chavín iconography was influenced by Cupisnique/Chavín religious tradition and represented one of the earliest and most apparent cases of religious integration in the Andes. The iconography was characterized by incorporating images of predators and predation into their depictions. Humans and birds would be represented with fangs, while different predators became popular motifs. Additionally, these non-human predator-like beings would be depicted in friezes and statues in and around ceremonial centers.

The most powerful of these ceremonial centers was Chavín de Huántar. However, during the transition from the Middle to the Late Formative (400 -1 BC), the theocratic systems, which had been predominant for hundreds of years, had been exhausted.

Ceremonial centers were desacralized and abandoned, including Chavín de Huántar. The once powerful theocratic governments gave way to more secular ones (governments based on political or military leadership).

This period of political transition was most clearly perceived in the north, north-central, and central coasts of Peru. The awe-inspiring high-scale architecture was replaced with populations resettling in clustered settlements (villages or towns) on defensive hilltops or fortresses.

Around 400 BC, coastal-highland interactions intensified and led to significant demographic shifts. Some regions saw population declines, while others were characterized by population growth.

Exactly what caused this shift remains unclear. However, scholars have proposed environmental, economic, and social factors, including conflict over scarce resources.

It is within this transitional phase between the Middle Formative and Late Formative (ca. 500–400 BC) that the QCC was used.

Located atop the slopes of the Cerro Mulato, along the left bank of the Supe River, this cemetery was first discovered and excavated in 2011. A total of 67 exceptionally preserved human burials were recovered across an area of 3500m2, that’s around 3/5th of an American football field.

According to Dr Pezo-Lanfranco, QCC provided a unique opportunity to study the bioarchaeology of children during the Formative Period,

‘The idea of studying the bioarchaeology of children from this period arose as a matter of opportunity. This is one of the few collections from that specific period (500–400 BCE) and one of the few fully excavated cemeteries from the Formative Period (3000–1 BCE).’

The buried individuals were placed in oval graves in flexed (fetal) positions. Most had limited grave goods, indicating the burials likely belonged to low-status individuals. Although, 48 individuals were associated with plain cotton fabric coverings or vegetal mats.

Others had been buried together with one or more gourds (Lagenaria sp.), pumpkin remains (Cucurbita sp.), cotton seeds (Gossypium barbadense), baskets, beaded necklaces, and pottery fragments.

Quite a few individuals, around 40%, also showed signs of intentional skull modification. When done correctly, shaping of the skull is relatively harmless. However, at QCC, three cases of skull modification had resulted in lethal damage, likely caused by excessive pressure caused by the modification device.

Sadly, of the 67 individuals buried, 47 of them were under the age of eight.

But how did these children die, and why did they die in such high numbers?

‘Children have historically been marginalized in bioarchaeological research for several reasons, such as poor preservation of their skeletons due to their inherent fragility, differential burial practices between adults and preadults, or anticivilization of this group by the archaeologists. Little is known about the paleopathology of preadults in prehistoric Peru, and this cemetery provided an interesting opportunity to examine the quality of life of these children,’ said Dr Pezo-Lanfranco.

Ironically, cemeteries often tell us more about an individual’s life than they do about their death.

At QCC, the researchers found that these children had short and very stressful lives, filled with diseases likely caused by malnutrition, poor sanitation, and overcrowding.

A Window into the Past

The 67 burials of QCC were meticulously analyzed, with a special focus on the 47 subadults. Interestingly, no individuals between the ages of 9 and 14 were found in the cemetery. Thus, the remaining 20 individuals represented over 15 year-olds.

Individuals were aged, and signs of physical and disease-related trauma and stress were recorded.

Due to the inherent difficulties of sexing subadults based on physical characteristics alone, all children were classified as ‘undetermined’ to avoid misidentification.

Age-at-death was determined by dental eruption (how many and how far along new teeth had formed), as well as vertebral development.

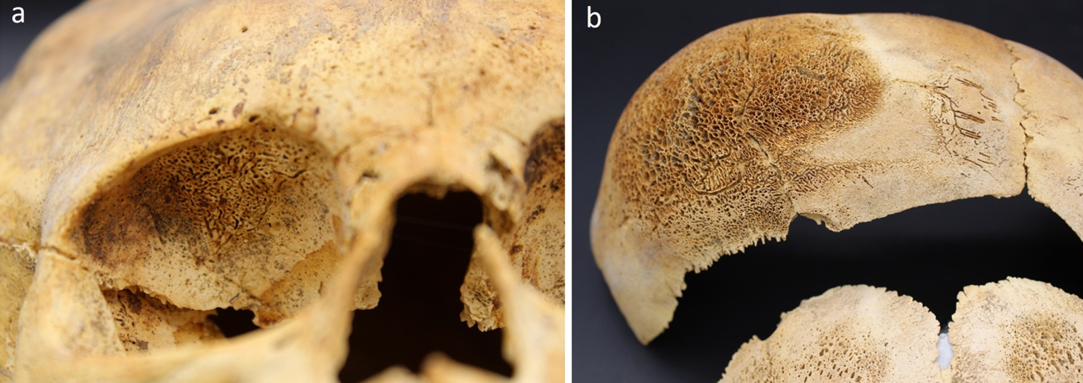

Next, stress markers were identified; these included cribra orbitalia (CO, eye-socket lesions often linked to anemia), porotic hyperostosis (PH, skull bone porosity linked to chronic anemia), periosteal reactions (PR, new bone formation caused by infection or inflammation), LEH and various other bone lesions.

A Life of Hardship and Disease

Sadly, these children and infants did not live carefree and healthy lives; the majority of bones showed various signs of health-disease-related stress. 85% of bones had PR, indicating severe inflammation or infection. These were particularly dangerous and potentially lethal for children below 3,5 years old.

Among those who survived into childhood, almost half (47,4%) had LEH, which formed between the ages of 2 and 5.

Others showed CO, associated with severe anemia, indicating these children lived through or died due to periods of severe nutritional deficiencies. Similarly, PH lesions on the skull signaled chronic anemia and systemic stress.

Some bones had other underlying changes potentially related to meningitis or systemic infections like tuberculosis (TB); these TB indicators were especially prevalent on the ribs and vertebrae.

Interestingly, most health conditions seemingly occurred before 3,5 years of age, after which chances of survival dramatically increased. In fact, babies and children were eight times more likely to develop any of the above health conditions than adults.

The researchers hypothesized this had to do with malnutrition coupled with poor sanitation,

‘High population density, lack of sanitation, and nutritional deficiencies are the most clearly related factors to this vulnerability. Imagine a poor community threatened by an apparently inter-community conflict, with high population density, malnourished adults (mothers), and a large number of infants and children demanding food. Malnourished children, exposed to infectious diseases and lacking proper sanitation, would have been extremely vulnerable to any additional stressors.’

Many of the individuals examined showed an incredibly high risk of developing these stress markers just before the age of one, around the same time when infants are no longer exclusively breastfed.

Around six to eight months, infants experience metabolic changes and are usually introduced to some solid foods, which provide various nutrients, including iron and vitamin B.

Weaning would continue until around 2,6 years, after which most individuals would have started exclusively eating solid foods. It was around this time at QCC that many of the children started to develop LEH patterns (aged 3,5).

Many archaeological sites have provided evidence of overcrowding, poor sanitation, and increased violence during the transitional period between the Middle and Late formative Periods. This violence was likely caused by warfare and conflict over limited and scarce resources.

With the historical context in mind, the researchers hypothesized that poor weaning strategies that included providing infants with inadequate or contaminated foods led to children not gaining enough of the essential macro and micronutrients, including iron and vitamin B.

This, in turn, led to chronic anemia and various other health complications.

Being so young, their immune systems had not fully developed. Thus, a disproportionate amount of children and infants died before reaching the age of 3,5 years.

But why was overcrowding, and poor nutrition a factor in the first place?

Malnutrition and Parasites

From isotopic studies on the bones, we know that individuals at QCC ate mainly tubers and cucurbits, with maize making up a small portion of the diet. Additionally, terrestrial and marine animals made up only an insignificant portion of their diet (<5%).

While in many Andean contexts, maize-based economies have been linked to high rates of anemia (as maize is a poor source of iron), this was not the case in QCC, as maize was not a staple food.

Therefore, researchers could not point to maize being the stable food of the QCC population as being the reason behind these high rates of anemia.

Instead, it is likely the lack of animal protein and consumption of plant foods poor in iron and vitamin B lead to chronic anemia.

Already weak from poor nutrition, these children also had to endure living in overcrowded and poorly sanitized environments.

Research of coprolites (fossilized fecal matter) in the Supe Valley shows various parasites associated with poor sanitation were the norm during this period of transition.

The parasites and bacteria found included E.coli, threadworm (Strongyloides stercoralis), giant roundworm (Ascaris lumbricoides), dog roundworm (Toxocara canis), head louse (Pediculus capiti), house dust mites (Sarcoptes dermatophagoides), and various other mites, lice and worms. Additionally, parasites that cause beaver feaver (Giardia lamblia) and dysentery (Entamoeba histolytica) were identified.

These parasites, usually associated with inadequate waste management and water contamination, cause diarrhea, blood loss, and micronutrient loss. Together with poor nutrition, any nutrients these children did receive may have been greatly reduced or lost from contracting other diseases and parasites.

It is possible (although still speculative) that overcrowding, poor sanitation, and subsequent poor nutrition were the result of repeated floods and landslides related to ENSO events (events related to El Niño-Southern Oscillations), which led to irregular water flow.

‘The Supe River has highly irregular flow, and it is possible that these people drank from springs or directly from the river, which may have been contaminated by upstream settlements with poor sanitation. A previous study has detected individuals infected with parasites associated with the use of contaminated water for crop irrigation. It is highly likely that the children in this farming community were exposed to gastrointestinal parasites, water scarcity, contaminated water, and intestinal infections, which could lead to potentially fatal diarrhea,’ explained Dr Pezo-Lanfranco.

People would have needed to congregate where food and water were more readily available, leading to overcrowding and violence (ca. 80% of adults and 12,8% of children at QCC showed signs of repeated and lethal trauma).

In such conditions, nearby water sources became filthy, and diseases spread easily. Any resources that did exist were likely stretched thin, leading to violent confrontations over scarce resources and favorable territory.

Many questions remain, and Dr. Pezo-Lanfranco hopes further research will provide answers. Did this phenomenon regarding childhood diseases occur in earlier times as well? Was this pattern exclusive to marginal and rural regions like QCC, and more broadly, what value did children have to prehistoric Andean societies

‘In Amazonian regions, for instance, the death of young children is more easily accepted, as they are not considered full persons until they reach a certain age. In the Andes, initiation rituals such as the first haircut — performed when a child develops their first teeth and begins weaning — suggest that personhood was only fully recognized after surviving infancy. Why? This could be a psychological protection mechanism for parents in societies where child mortality was common and normalized.’

Although we tend to view many aspects of the past with rose-colored glasses, studies like the one above remind us that life in the past could be harsh and brutal. Today, if you have anemia, you can easily go to the pharmacy and buy iron supplements or incorporate more spinach and red meats into your diet.

However, for the Formative Period QCC individuals, this was not an option. Forced to live in overcrowded and unsanitary conditions (possibly due to environmental factors), adults and children alike faced nutritional deficiencies exacerbated by parasitic infections and chronic illnesses.

The most vulnerable members of society, children and infants, were hit the hardest.

An especially critical stage in life was the weaning period, when infants transitioned to solid foods. Given the poor nutritional value or contamination of these foods and water sources, many did not survive this phase of life.

The study by Dr. Pezo-Lanfranco and colleagues reveals more than just the grim reality of life during the Transformative Period; it is a testament to the remarkable resilience of human communities. It provides us with glimpses into the survival and resilience of adults and children during the Transformative Period in QCC.

Today, finding such incredibly severe bone markers of stress and disease is much rarer (thankfully). However, I still wonder what could have caused that single LEH line on my friend’s tooth.

What do you think caused the transition from theocratic to secular systems of government, and what factors may have forced people to live in such overcrowded conditions that led to poor sanitation and health?

Let me know your thoughts, and if you’d like to support me further, why not Buy Me A Coffee

References

Ikehara-Tsukayama, H. C. (2023). The Cupisnique-Chavín Religious Tradition in the Andes. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Anthropology. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190854584.013.448

Pezo‐Lanfranco, L., Barreto, M. I., Filippini, J., Silva, K., Crispín, A., Machacuay, M., Nova, P., & Shady, R. (2025). Preadult Living Conditions During Sociopolitical Transition in Quebrada Chupacigarro Cemetery (500–400 bc), Supe Valley, Peru: Childhood Morbidity and Sociopolitical Change in Prehistoric Central Andes. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, e3386. https://doi.org/10.1002/oa.3386

Pezo-Lanfranco, L., Romero, M. I. B., Filippini, J., Crispín, A., Machacuay, M., Novoa, P., & Shady, R. (2024). Bioarchaeological Evidence of Violence between the Middle and Late Formative (500–400 BC) in the Peruvian North-Central Coast. Latin American Antiquity, 1–17. DOI: 10.1017/laq.2023.38