The ‘Mad Cow Disease’ scandal, or Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE), remains a stark reminder of the devastating consequences when public health is compromised. This article delves into the timeline of events, the governmental missteps, and the personal tragedies that unfolded during this crisis. Understanding the lessons learned from this scandal is crucial for preventing similar disasters in the future.

From the initial discovery of BSE in British cattle to the emergence of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD) in humans, the ‘Mad Cow Disease’ scandal exposed critical flaws in food safety regulations and government transparency. The impact was far-reaching, affecting not only the health of individuals but also the economic stability of the beef industry. This article aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the key events, the science behind the disease, and the ongoing concerns about potential future outbreaks.

We will explore the origins of BSE, the use of mechanically recovered meat, the government’s response, and the heart-wrenching stories of vCJD victims. By examining these aspects, we can gain a deeper understanding of the complexities of this public health crisis and the importance of vigilance in safeguarding our food supply.

The Origins of Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE)

The story begins in 1984 when Cow 133 on Stent Farm in Sussex, England, exhibited unusual symptoms. The cow’s head trembled, and it suffered from a loss of coordination. After its death in February 1985, an autopsy revealed the cow had died of spongiform encephalopathy. By the end of 1986, Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy, or BSE, commonly known as Mad Cow Disease, was officially acknowledged.

Investigations revealed that cattle likely contracted BSE from meat and bone meal, a cattle feed made from animal carcasses, including cows. This practice, forcing herbivores to consume their own species, led to the spread of the disease. In July 1988, the UK government banned meat and bone meal from cattle feed. By then, an estimated one million infected cows had entered the human food chain.

Initially, it was assumed that BSE was not transmittable to humans, based on the long history of humans consuming sheep infected with scrapie without apparent harm. However, this assumption would soon be challenged.

Mechanically Recovered Meat and the Risk to Public Health

During the 1980s, mechanically recovered meat (MRM) from cow carcasses was used in foods like sausages, burgers, and meat pies. MRM often contained brain matter and spinal cords, the most infectious parts of a BSE-infected cow carcass. Unaware of this, the public unknowingly consumed this risky by-product.

School children were particularly vulnerable. In 1980, the UK government removed nutritional requirements for school lunches, leading private companies to serve the cheapest options, often made from MRM, which was significantly cheaper than other meat products. By 1990, an entire generation of British children was exposed to potentially contaminated beef.

While school children faced greater exposure, anyone consuming British beef was at risk, highlighting a widespread public health failure.

The Government’s Insistence on Beef Safety

Despite the BSE outbreak, the Conservative government maintained that British beef was safe to eat. Microbiologists Prof. Richard Lacey and Dr. Stephen Dealler dissented, arguing that BSE-infected beef could cause Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD) in humans.

Lacey, a vocal critic, called for the slaughter of six million cattle. Dealler warned on TV that the British public had already consumed 1.5 million infected cattle. Both faced backlash, with Dealler removed from his research lab. In June 1990, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher declared in Parliament, “British beef is safe.”

The financial interests of the beef industry were prioritized over public health, leading to further risks and eventual tragedy.

Evidence of the Disease Jumping Species

In May 1990, a BSE-type illness killed Max, a Siamese cat fed on beef, demonstrating the disease could cross species. That year, 15 more cats died of feline BSE, and the disease was discovered in fourteen other species. Fears that BSE would also cross to humans grew, but were suppressed by the government.

This evidence further undermined the government’s claims of beef safety and heightened concerns about the potential human impact.

The First Confirmed vCJD Death: Stephen Churchill

In August 1994, 18-year-old Stephen Churchill crashed his car and subsequently developed a rapidly progressing neurological illness. Diagnosed with Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD) in February 1995, he died that May, becoming the first confirmed death in the UK from new variant CJD (vCJD).

Almost a year later, in March 1996, the government finally admitted that eating BSE-contaminated beef could cause vCJD in humans. This admission came after years of denial and downplaying the risks.

The Human Toll: Victims of vCJD

By the end of 1996, thirteen people had died from vCJD in the UK. The BBC’s Panorama highlighted the devastating impact of the disease, featuring victims like Donna Fellowship, who was unable to move or speak. The program also showcased Pamela Beyless, whose memory was akin to someone with mid-stage dementia at just 22 years old.

The year 2000 saw a peak in vCJD deaths, with 28 people dying. Victims included schoolgirl Claire McVey, who died at 15, and Sally Evans, who died seven months after giving birth to a daughter with brain damage.

These personal stories underscore the human cost of the ‘Mad Cow Disease’ scandal and the long-lasting impact on affected families.

Long-Term Concerns and the Possibility of a Second Wave

As of January 2015, there have been 226 confirmed deaths from vCJD worldwide, with 177 occurring in the UK. All cases have occurred in people born in 1989 or earlier. However, concerns remain about a potential second wave of vCJD cases.

The most recent UK death from vCJD occurred in 2016 and involved a victim with a different genotype than previous cases. This raises fears that more deaths are imminent among those with this genotype, which represents 51% of the UK population.

Additionally, some cases of sporadic CJD may in fact have been vCJD, and deaths from vCJD in older people may have been missed due to lack of post-mortem examinations.

Blood Contamination and Restrictions on Blood Donations

vCJD is present in an infected person’s blood, leading to concerns about blood transfusions. By 2004, four people who received blood transfusions from donors who later died of vCJD had also died of the disease.

Many countries have banned blood donations from individuals who spent significant time in the UK between 1980 and 1996. Despite blood donation shortages, these restrictions remain in place due to the lack of a test for vCJD in donated blood.

The Legacy of the Scandal and the Quest for Justice

A 2013 study estimated that one in every 2,000 people in the UK may be a carrier of vCJD. There is still no effective treatment or cure for the disease.

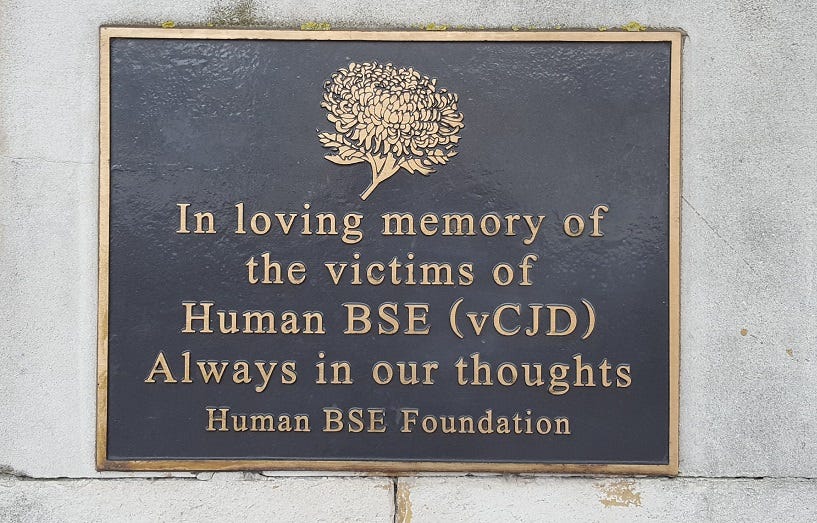

Families of vCJD victims express feelings of betrayal and a lack of accountability. The founder of the Human BSE Foundation, Francis Hall, describes the sense that their children were “murdered, yet nobody is going to be punished or even apologise.”

The ‘Mad Cow Disease’ scandal remains a cautionary tale of the consequences of prioritizing economic interests over public health.

Conclusion: Lessons Learned and the Path Forward

The ‘Mad Cow Disease’ scandal serves as a critical lesson in public health, government accountability, and food safety. The decisions made during the crisis had devastating consequences, leading to numerous deaths and long-lasting health concerns.

Key takeaways from the scandal include the importance of transparent communication, rigorous testing and monitoring, and prioritizing public health over economic interests. The story of Stephen Churchill and countless others highlights the urgent need for robust food safety regulations and vigilant oversight.

As Annie McVey reminds those in positions of power, their choices have consequences. By learning from the mistakes of the past, we can strive to prevent similar tragedies and ensure a safer future for all.